ASKING THE MASTERS - Material ART

In this series, Kieran Goodson reveals what he learned from the most reputable artists in the industry, allowing us deep insight into their areas of expertise. In this Material Art edition, Kieran explores vital topics from material creation for games vs portfolio, challenges of material art, presentation and much more. You're guaranteed some pocket-sized wisdom to take home.

Introduction

Material art. Texture art. Surfacing art. Whatever the studio calls the role, it’s a position that in recent years has been launched into the limelight by many of the artists we’re going to be talking to here.

Today we’ll be confronting the biggest challenges of material art, venturing into the craft for answers and searching for clues in the cracks between portfolio and production artwork. We’ll be finding out what advice veteran artists have after spending ten plus years in the business and taking on board the lessons they’ve learnt along the way. As a result, we’ll learn where artists need to adapt, how we can solidify this newfound knowledge in the form of content and peek at what awaits us on the next-gen horizon.

My name is Kieran Goodson and I’m a Junior Environment Artist at Rebellion. When I’m not that, I’m usually scribing for my blog, getting wrapped up in industry conversations or posting to my other socials - Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Without sounding too much like an Amazon recommendation, if you like the sound of this article, you may also enjoy the environment art or the lighting art editions that I’ve published. But without further ado, welcome to ‘Asking the Masters of Material Art’.

ONCE UPON A TIME THERE WAS A MATERIAL ARTIST...

We’ll begin with Ana M Rodriguez, Senior Environment and Material Artist at Counterplay Games who kindly sets the scene and describes the day-to-day of the job.

What does the typical day job of a modern material artist look like?

“Well the typical day for a material artist is a mix between looking for information and an approach about what you are trying to do next, and starting to do a blockout for it. I don't think it differs much from the day of a character modeler or an environment modeler in the sense that for me, working with Designer has its part of “sculpting” the forms and then “painting” them. Apart from that, there is always the remaining part of your job focusing on really testing what you are doing in the engine... because visually this is where you really want that material to look at its best. The portfolio is a very good and valuable thing to maintain, but the aspiration of a material artist should be that this material looks its best in the environment or environments where it is intended to be. Back in the days this was more difficult because the conditions changed radically from one environment to another and an artist had to learn to "cheat" a little with the texture things that technology was not able to achieve. Today luckily thanks to PBR if a material behaves correctly it should respond well to wherever its final destination in the environment will be.”

You’ve been a texture artist for 15 years. Can you talk a bit about how the artform has changed over the years?

“Well, according to my memory things were not very easy when I started, at least not when it comes to learning possibilities. I started this as a result of a master’s degree and now there are dozens. Back then specialized forums were hard to find while today there are hundreds of them, in addition to tutorials and masterclasses with very skilled professional people from the industry involved.

It is very gratifying to know that you are going to have that obstacle overcome from the beginning, but in this sea of information that we now have, we must understand that it is difficult for someone who begins to separate what is really valid from what is not so much. I think this is one of the obstacles of today's learning process, that someone from a very early age or stage in this industry needs to know how to differentiate between what they want or should learn, what will be useful in the future, what will not be, and from whom the information is coming from.

When I started there were also less people and now the competition and the level of demand is high. It doesn’t mean that before it was easier, but we already started from the fact that whoever aspired to this was because they would have to work hard. Nothing was gifted. It is not a race to sit comfortably and wait for the days to pass, it requires continuous learning and effort in an industry that advances quite fast. Over the years I have had to completely change my learning process. If we talk directly about material creation for games, when I started the normal map did not even exist. Both bump or displacement maps were done entirely by hand painting a grayscale mask. You think about it now and that work is practically handmade like a wood-carving or something.

Normal maps and ZBrush arrived and totally changed the way of approaching work, and that was a constant renewal and dying mentality (and for me it continues to be). You are comfortably sitting in your chair and suddenly, BAM, Allegorithmic and their Substance Designer / Painter emerge to remove the foundations of what you had learned.

This doesn’t mean that the tool surpasses the artist, but the artist has to take their skills and adapt them to a new software with a totally different philosophy and approach than he / she was used to in order to achieve the highest level of quality. So, it's clear that if you really like this job... forget about sitting on the couch for at least the next 15 years.

Or at least, this is my advice.”

What are the biggest road-blocks for material art at this moment in time?

“About the ‘road-blocks’ - making UV’s is horrendous? Well, not for me particularly. Sometimes it is zen and is mechanical work that I even find relaxing.

But if we talk particularly about textures I think that indeed there is even more scope to give more creative freedom to the artist in his / her work. There is a bunch of work on a daily basis that is very mechanical and could be automated for sure. I can think of hundreds of nodes that Designer could do to make my life easier without having to generate them (a lot has been achieved with this thanks to embracing the proceduralization but there is still a lot to do). I think as “technical” artists that the majority of us are (I’m not saying that we are “technical artists” per se but we need to bend some technical aspects in our daily basis), there are inevitable things that will arise now or will continue to arise in the future that will require more mechanical than artistic work from our part.

There are a lot of complex processes involved in making games that we cannot avoid. Yes, we have “artist” in the title but we are far from being bohemian in that aspect. We do technical work, we implement things in an engine and this engine constantly evolves of course, but it will always have its limitations and there will always be ways of taking advantage of the same limitations. I don’t think this should be a handicap. One should always take this as an opportunity to explore things in a different way.

This reminds me a lot of the issue of the fog in Silent Hill for example. You can't render things in the distance so you create a fog, then you cover this with this mystical mythology about a ghost town and there you go, your limitation is your hallmark identity.

I think the definition of a video game artist is this: you overcome your limitations and you constantly transform them into your strong points.”

GETTING PAST THE ROADBLOCKS

The scene is set. The job is tricky and like everything, it has its own set of issues: UV's can be boring; nodes in Designer are yet to be born to automate many processes and it's hard to recreate complex materials while keeping everything readable.

Are there fundamentals out there to help us? There have to be some nice workarounds to the regular bugbears of material art. I caught up with Environment Texture Artist at Naughty Dog, Chris Hodgson to see if he had any tips for us.

What are the trickier phases of the material creation process and how do you get round them?

“With complex materials that have lots of detail or many different elements, it can be tricky figuring out what details you really need to replicate, and the ones you don't. In order to keep the material readable and avoid noise I try to identify the components that have a significant contribution to the materials look, starting with the largest forms and working my way down to pores and particles. Any details that will end up close to or sub-pixel in size I tend to leave out, especially if it is going to be used in a game engine.“

“Creating a really natural looking dirt and grime pass on materials can be a real back and forth process that's difficult to get right the first time. There is a tendency for people to try and achieve all their dirt with one layer or single blend of a dark color. I prefer to layer up many subtle layers of light dust and dark dirt with masks at low opacities to build up the age of the material slowly. It takes longer and requires more tweaking but it ultimately produces a much more realistic looking material that really has some history to it.”

Are there any neat tricks that you love to do when working in Substance Designer?

“I use ambient occlusion nodes throughout my graph constantly, not just at the end plugged into an output. It's such a useful way to mask out wear and tear as well as the dust and dirt I mentioned before. Inverting your height information before you plug it into an ambient occlusion node will also give you the convex areas or extremities of your materials surface rather than the occluded crevices you would normally expect. Using the AO node this way is invaluable and I recommend people try it out.”

“The Height Map Frequencies Mapper node is something I have started to use a lot lately. It allows you to regulate the frequency of details in an input much like High Pass, but at a much higher quality. I use it all the time with many of the built-in grunge nodes that Substance Designer ships with. Sometimes those grunge nodes have too much low frequency detail in them that makes them tile poorly, running them through the Height Map Frequencies Mapper will fix that right up so you can make textures that tile great and you’ll get more use out of the default nodes without resorting to creating new ones.”

What's your favourite material of yours and why?

“I think my favorite material is a painted cinder block material I created in 2019. It’s a great example of my favourite aspects of texturing: replicating the subtleties and nuances of real world surfaces in my artwork. I’m generally a big fan of this kind of work because it pushes me to improve my texturing ability and in the end gives me a better understanding and appreciation for how the real world is constructed. Really nailing the details in materials that a lot of people might miss gives me a great sense of satisfaction and with the cinderblock material I think I just about managed it.”

“Start with the macro and work your way down into the micro-detail. Using the AO and Height Map Frequencies Mapper nodes to drive your masks and polish up those default grunges. Figure out the subtleties of a material and replicate them. Chris does an amazing job of simplifying the process for us and it made me wonder - does this advice work for every task? After chatting to Enrico Tammekänd, Environment Artist at Counterplay Games, I picked his brain about a “standardised approach” to materials.”

A STANDARDISED APPROACH & PRESENTATION

You’ve tackled a huge range of materials so is there something you’ve noticed that they all have in common? Do you find yourself approaching each material with the same workflow?

“Actually yes. Even though it might seem like a small detail, I think it's very crucial to build your materials with only mid-grey in the base color and roughness, and only focussing on the heightmap. If you start to create materials with all the maps together, you will lose the sight of what you wanted to achieve. The same principle would apply if you know that you will have a flat material that relies mostly on albedo, then don't try to add extra details in the height, normal or roughness maps before you are satisfied with how your base color looks. I believe that helps out a lot to define the right characteristics for the materials and not get distracted from the references. Also, add a stronger normal map intensity. Trust me, it will make your materials look much richer and you can always lower it according to the needs.”

Do you think it’s important to show materials in a real-time environment or is Marmoset just fine?

“Well Marmoset Toolbag already is a real-time rendering engine so it's fine to showcase your materials there. In the end, it's your artwork, especially with personal projects, so it's best to show off as much as you can. Every studio has their own technical guidelines that you need to follow. Lighting and post-processing will alter your original material so therefore it doesn't matter as much if you show them in-engine or just in a Toolbag. It's always a plus to show that you didn't just create one variation of the material, but multiple presets that can be vertex blended in the engine. That said, I would recommend showcasing the materials on an actual environment or prop rather than just how it looks in the engine on a sphere. Honestly, it's the artist’s own choice and in which type of industry they specialize in. I would suggest VRay if you do architectural materials as that would be the main usage and it needs to look good there.”

Balls, planes, rounded cylinders. Every artist presents their materials differently. I’ve noticed that you present yours on spheres with neutral lighting and a transparent background. Why do you do this?

“I like to render on spheres because you can see the material and it's tessellation on both a flat surface (when looking straight at it) at the same time as on a curved surface (from the sides). You can observe so much more than just a planar render for example. If you imagine your material being used on a terrain, you need to know that it won't cause any tessellation problems since the subdivisions there are usually very low and irregular surfaces.

Regarding consistent color as a background, I find that it helps to relax the eyes and not distract from the artwork itself. And of course it makes the portfolio look much more cohesive.”

Enrico’s consistent presentation style is one that catches my eye every time and allows you to analyse how a material reacts to its surroundings without getting distracted by crazy backgrounds or neon ambient light. While we’re at it, what other presentation advice is out there, not just for materials, but for props and environments too. Another artist who does this incredibly well is Michel Kooper, the Lead Environment Artist at PUBG Special Projects Division.

The Hunt Showdown art drop features some of the best presented environments, materials and props that I’ve seen. What words of advice do you have for artists when it comes to presentation?

“Keep your backgrounds in mind!

Although not really the center of attention, backgrounds do play a role in the presentation of single assets and materials, a background too dark or too bright might throw off your perception of how the model is lit. For example, if the background is too bright the shadow side on your lit prop might read as too dark, even though there’s plenty of information in the render.

This example below wonderfully illustrates this effect.”

“You can use this effect to bring up or tone down things in your presentation. In a lot of cases I’d recommend starting with something of a mid grey value, and from there make tweaks in brightness. You can introduce some color to compliment the asset or material. Brighter or darker, if used deliberately can help with the presentation. For my Hunt materials I went for a darker background with some vignetting to make the center pop.

It’s easy to get caught up in the process of editing your background. While working it’s important to toggle some of those effects on and off and honestly ask yourself is this adding anything? Often, you’ll find that the simpler cleaner backgrounds will keep the focus on the asset or material and with a bit of intent can help it shine.”

“One last thing on backgrounds, if you are presenting a set of images that belong together try and use a consistent background or scene/camera angle for each shot, it will tie things together and between shots will keep the focus on the subject you are presenting.”

Embed stories in your scenes

“This is not so much presentation as it is environment art in general but when presenting scenes, try to embed the story into it. The way you place your props and decals go a long way in selling the scene. Scene composition and “leading the eye” are important tools. Allowing the viewer to pick up details along the way that help sell and solidify the setting and world will make good composition and player leading extra powerful. More importantly, games are an interactive medium - players decide where to look so you’ll have to help them along. I must give a shout out to the teams working on The Division 2 as that game is so densely layered in world building and storytelling elements it’s just an amazing environment to play through and explore, especially the mission areas.

For Hunt: Showdown we did visual explorations for the interior spaces and used the same approach. Working towards a theme and aligning elements like props, decals, asset placement, VFX and lighting to help set the mood, tell little stories and let the player piece together the events that have transpired before their arrival.”

Use decent image resolution

“In this day and age, I don’t think there’s anyone using monitors and screens that are less than full HD in resolution. Keep this in mind when taking your shots. 2K and 4K monitors are becoming more common. I’m not saying make every shot 8k, but you’ll want to find a resolution that will hold up for a while.”

Keep an eye on your lighting

“Keep an eye on your lighting, contrast, exposure etc. Avoid crushing your blacks or blowing out your image with bright hotspots that draw too much attention. Always test your images on a variety of displays. You might be keeping up with your monitor calibrations but that doesn’t guarantee your image will be viewed on a perfectly calibrated monitor (odds are, it will not be). It’s good practice to have a look at your image on a variety of screens, look at it on your iPad, throw it up on your tv, etc. Make sure you are happy with the image regardless of the screen you view it on.”

So that’s an awesome checklist for making sure your renders and presentation skills are hitting the mark. Presentation is such an underrated area in my opinion and it makes all the difference. I cover this a little bit in the first part of my Guide to Game Art Applications. It’s recommended you cut down your portfolio to your best work and by making sure each render has a motivation behind it - a new perspective, a new point of interest or showing an asset in isolation as some examples.

We’ve tackled some of the main challenges outlined in the intro. Just like James Bond at the start of most 007 movies, we’ve been given some new toys from the talented artists we’ve already spoken to. Decent Designer nodes to integrate into our workflow. A standardised structure to approach materials from any angle and a dosage of practical presentation techniques to inject into our next piece. However, there’s a mission. The mission is now to figure out what the hell to do with it all. The villain in the room is a topic of conversation that comes up no matter the game art discipline and it dictates the mission plan.

THE RIFT BETWEEN PORTFOLIOS AND PRODUCTION

While you’re exercising the same skills for both, the mentality and the way you approach work drastically changes when you’re making a fully fledged real-time game compared to a portfolio piece. I wanted to dive into this with those who know most about it.

The next segment will feature ideas about this from Javier Perez, Derk Elshof and Eric Wiley. But first, we’re tackling portfolios with Senior Environment Artist at Counterplay Games, Alex Beddows.

Is there a checklist you have when you’re contributing materials to your portfolio?

“Most materials I tackle are for an objective reason, whether it be testing a new workflow, trying out some new nodes or demonstrating my ability to do a particular type of material. For example, recently I have been leveraging Blender physics to create a rubble pile material and cloth simulation assets like I normally would in Marvelous Designer.

I treat all projects in this way as it helps me know the criteria for completion and it feels way more productive, that's why when I do some material that I have done previously I tend to drag my feet a little because I get bored due to solving the same problems as before.”

Three Substance Designer nodes: Guilty pleasure, can't live without, try to avoid. Go.

Guilty pleasure - Slope Blur

“I am not sure if it is a guilty pleasure or not but Slope Blur. It's such a powerful node and gives very quick and easy results. But that's kind of the problem, it's very easy to plug your shape into it being distorted by ‘Clouds 2’ and call it done. The trick with the node is going the extra mile and refining the shapes you create and not push it too far, you can spot the jagged slope blur stepping a mile off!”

Can’t live without - Non-Uniform Directional Warp

“This I simply can’t live without. Pretty much any noise or surface detail can look wrong when it is just blended on top of the base shape, the Non-Uniform Directional Warp helps make the noise detail feel influenced by the underlying shapes. This was some feedback I received early in my material art progression and it felt like one of the big step ups for my development.”

Try to avoid - The default grunge textures

“Kind of similar to the Slope Blur, they are quick fixes and easy solutions, but very rarely do they reflect the surface you are trying to capture. However, using them as a base that you work into so that you can create your own unique grunge is how I think these noises should be leveraged.”

Your portfolio materials: the same question.

Guilty pleasure - Crew Collective Café Ceiling, Montreal

“This type of material is a self-serving endeavour. In production, displacement-dependent materials like the crew collective ceiling and many of my other materials do not really exist, however they are great personal experiments. Not only do they look cool but you get to develop your control over height and work with multiple components that make up that material.”

Can’t live without - Padded Space Bag Material

“The space padded material is kind of a mental shift in how I perceived materials. Up until this point I was so hung up on 100% Designer everything and seeing James Ritossa do some fantastic Marvelous work in his SD materials made me want to try it. It came out great and I was thrilled, however I felt a lack of pride in it due to not creating everything in Designer. Looking back it’s such a toxic and destructive mindset and luckily I spoke to Ben Wilson quite a lot about this and he really helped dispel this idea and he explained how using outside packages shows just how much you know about SD as I understand its limitations and when it is quicker and more effective to leverage another package.”

Try to avoid - #Nodevember stylised crystal study

“God this was a hack. I wanted to replicate the exact shapes in the original painted texture, but was struggling to get close with the crystal placement so I ended up transforming a bunch of shapes into place which is just not a good way to tackle it. I figured out a couple of interesting workflows and tricks with this one but it was by no means clean.”

And are there materials you’d recommend everyone tries at least once?

“I think there are two types of materials - production showcase and skill showcase.

Production showcase materials are, in my opinion, you are showing off the traits you use in game production, such as creating multiple materials that belong and work together, showing your control over big macro-shape materials or making the micro-detail materials readable. Practical skills that transfer directly into the studio day-to-day.

Then there are skill showcase materials. These are the ones which might not necessarily be relevant to a day-to-day job of a materials artist, for example the ornate ceiling materials I created. This is me demonstrating my control over height and the ability to really create complex shapes. I think trying to do both these types of materials will help round out your skillset.

Lastly I’d say don't get caught up in the 100% Designer mindset because a lot of the time it is nothing but a flex. Since leveraging outside resources like Blender, ZBrush and Megascans, the quality vs time investment has gone through the roof and this is the true nature of game production. Getting high quality in reasonable time. The sooner you break that 100% Designer constraint, the more you will see your material art grow.”

Now the more of the same topic, but with Senior Material Artist at PlayStation VASG, Javier Perez.

Work such as 'Tiki', 'Not the Bees' and 'Viking Axe' are awesome. Do you think that in the future crazy materials like these will have a home in full game production? Can you think of any examples where these might be more efficient to create than modelling, baking and texturing an asset from scratch?

“It's hard to say whether these kinds of materials can be used in full game production. When creating these sorts of materials, the only way they are able to work is because of the heavily tessellated mesh they are applied to. Sometimes the meshes are so heavily tessellated the polycount could be as high as a full environment, which is definitely not a good practice as far as a single asset goes. That being said, there are ways to integrate something like those objects in game. For example, the axe heightmap could be taken into ZBrush, extruded out and decimated to produce a full 3D object.”

What were the main challenges creating materials for The Last of Us Part II and the huge expectations from the franchise?

“Keeping material and textures counts down has always been a challenge with any game I’ve worked on, and The Last of Us Part II was no exception. Making sure material counts were as low as possible while still being able to keep the fidelity of the different blends we could utilize within an area was always important.”

The crazy portfolio materials are great showcases of skill in Designer, no one questions that. But production is clearly very different. I’m not sure how transparent these differences are to newer artists just starting out so I spoke to Derk Elshof, a Junior Material Artist who joined Ubisoft Massive this year. I wanted to hear how he prepared his portfolio to get the AAA job and what his expectations of the industry, and subsequently production, were.

ADAPTING TO AAA

Derk, what should people expect when joining a AAA studio as a Junior?

“I think if you are hired they know you can achieve the quality they are looking for, only it takes more time to get to that level. In my case it definitely took some time to adjust my workflow and get up to speed.

In terms of material creation, it would be helpful to test out your materials as quick as possible to check out the shapes and scale of things to know if it will work in context or not before heading into adding all kinds of details that can really consume a lot of time that could be for nothing.”

Firstly, you’re one of the few who I’ve seen go back to your older portfolio work to remaster it. What mistakes had you made on the first iteration of “Grass with Birch Leaves”?

“I derived my normals from the heightmap and in cases of foliage that isn’t always ideal since it can give a lot of jagged edges when displacing. Blending the normals in separately gives a lot more control to fake the depth in the material while still retaining good displacement.

If I would remake this material again I would be looking into using atlases with the use of the Atlas Scatter node and avoid doing foliage procedurally. It makes it a lot easier to test out different foliage types and include leaves or branches from trees or bushes you might have made. The atlas node also makes it super easy to offset the color and roughness values and change the normal orientation on each leaf to achieve something that looks more realistic.”

What were you improving?

“1. The first thing that bothered me is that the leaves in the first iteration [left] felt like it was all merged together. They are all facing upwards in the normal and adding some rotation created a lot more depth in the material while still retaining good displacement.

2. Introducing the small white pebbles in the soil made the dirt more readable. Before it might as well have been a pile of old leaves instead of dirt. The eye-catching bright pebbles made the dirt stand out and will most likely hold up when there isn’t any foliage scattered on top of it.

3. Adding more grass and backside leaves pushed the range of both the hue and saturation and added more complementary colors to the material. It created a sense of layering where as before it feels to be all the same thing.”

Finally, in your Birthday Boy scene, you talk about pushing roughness values to make things pop in-engine. What are your thoughts on breaking PBR in order to achieve a specific art direction?

“PBR is merely a guideline to get a believable looking material, but in a game engine we might not capture all the details we want as an offline renderer like V-Ray or Redshift does. Pushing the variation in both the color and roughness is almost necessary to make certain shapes stand out more and make it look good in multiple lighting conditions.

In flat lighting conditions your material might not be readable since the normal and roughness map might not do anything at that point. For instance adding AO in both the color and roughness can help out a lot in those cases. I wouldn’t disobey PBR values, just choosing values within an acceptable range to give the most variation as possible within each texture map.”

It’s important that we follow the guidelines of PBR as a base standard and then break it if needed to meet the requirements of readability and art direction. Therefore, the juicy detail you might be adding into your materials for your portfolio, captured in an offline renderer or bells-and-whistles engine like Marmoset might not be appropriate, or even usable, in a real-time environment for games.

This all begs another question: Is portfolio work misrepresentative of what an artist can do in production and if so, is that a problem? Eric Wiley, Environment Artist at Blizzard Entertainment who has had over a decade of experience in the industry enlightened me.

What are the main differences between portfolio materials and those created for game production? Do these differences cause issues when it comes to hiring?

“The two main differences that come to mind right away are material balls and strictly using one software package.

When you are making a material just for your portfolio you can turn on all the bells and whistles that might not be available in a game production especially when performance is king. It's 2020 and still the vast majority of games don't have real time tessellation and displacement. When you are just rendering a ball in Marmoset for example, it's easy to hide any issues with your material. It can be difficult to tell how well a texture tiles, does it read at a variety of distances or have a visual hierarchy? I'd encourage artists to build a small scene to showcase their materials whenever possible.

That said, I do think experienced material artists can still tell good materials from the bad just by looking at the ball render so it is definitely possible to land a job that way. One thing that I'm definitely guilty of is making materials 100% in Substance for my portfolio but in actual game production there are definitely some things I could do faster in ZBrush or Maya. These 100% Substance Designer stamp approved materials are great at showing what is possible as well as being a ton of fun to make but are not always feasible when you have a deadline.”

Do you think material artists and environment artists are built differently? Apart from knowledge in software, are there qualities that aren’t mutually exclusive?

“In many cases I feel that the best material artists actually started as environment artists.

I feel it's invaluable to have the experience of modelling and building the environment, understanding how textures will be used in context and what makes for good blending and tiling. There is a ton of overlap but I feel that the main difference is that material artists are very specialized and support many artists across the studio.

I think it's important for a material artist to look beyond the specific environment they may be supporting at the time and make materials or parts of graphs that can be reused in other areas of the game or even by the character and VFX teams. Having material specific artists can also help raise the quality and consistency throughout the game.”

Eric raises a brilliant point. The material artist role seems to sit somewhere nicely between tech art and environment art and a lot of the job is about supporting the wider team. The modern rhetoric about being a material artist is that the role can be quite rare to find, especially at entry-level and it’s recommended that you specialise as a tech or environment artist beforehand. That being said, with the folks featured in this article doing a brilliant job of inspiring the next generation to get involved with material creation, that could very well change. Having experience in either is invaluable to wear the material artist hat.

Speaking of hats, someone who has worn many art during his time in the industry is Ben Wilson, Material Artist at Ubisoft Stockholm. I don’t mean that literally - he’s a rare gem that has been employed in so many different areas of game art over the years. Because of this, I implore you to give this section its due diligence because his answers are packed with a metric tonne of, not only work, but life advice too.

A DECADE IN AAA

Ben, you’ve worked on racing, combat and action-adventure games with compelling stories, both first and third person. On top of that you’ve been a tech artist, environment artist and now a dedicated material artist. If you had one takeaway from each of your shipped titles, what would they be?

“This is an interesting question that made me think a lot. My first studio job was at Playground Games, which I managed to get just after graduating from university. At this point I had spent most of my teens aspiring to game development and the majority of my free time went into this. It was quite all consuming actually and perhaps a little unhealthy. When I got the Playground Games job, I remember being overwhelmed with a feeling of ‘now what’. This was certainly not something I expected to feel. I had worked for so long trying to reach this goal, that I realized I didn’t really have anything else to define myself with. Suddenly losing my main driver in life, kinda left me a little lost. The guilt soon followed for not feeling happy at finally making it, after all, I should have been over the moon, right? So I think I ended up throwing myself into work even more. I wanted to impress and do a good job, so I did an awful lot of overtime. We were crunching for a long time, at heavy hours and I ended up becoming very ill as a result. It took me years to recover and something I see happen very often with fresh artists in the industry.

My biggest take away of all my career was probably this and it happened right at the start. The importance of balancing yourself and not getting tunnel vision. Please, do not feel guilty when you binge on that Netflix show! As long as you’re progressing year-to-year, you do not need to kill yourself day-to-day.”

“I joined Crytek some time after that to work on Homefront and learned an important lesson here too - objectivity. I was at Crytek UK for a brief time before the studio shut down and despite only being there for 6 months, it opened a lot of doors for me. Suddenly I had a surge in job opportunities and was starting to be taken seriously when applying to jobs. Really, I was the same artist as when I had joined Crytek. I was there only a few months, many of which were not actively working due to the payroll issues and frankly the stress made personal development the lowest of my priorities. However, the Crytek name drastically increased my market value. For better or worse, people were quick to judge and thankfully this ended up being a big positive for me. Everyone thought I must be good if I came from Crytek! Really, I was only lucky and just as crap as before.”

“The Division was the first game where the average person might have heard of a game I‘ve worked on and I had a wonderful time being part of it. I definitely learned a lot here too, especially having moved abroad for the job. Following from my previous point, you often hear people complaining about why things are like this or that. "Why did that person make this asset that way, it’s crap", "Why don't they just do this instead". These kinds of things … I'm sure most readers will be familiar with at least one person in their lives like this. We all behave like this from time to time, it’s normal. There was one individual at work that I had a fairly low opinion of. Then of course, I was tasked to work with them... Given this, I thought it would be important to build a better relationship, so I spent some time sitting down with them, understanding why certain decisions were made and what was going on. It quickly became apparent that I grossly misunderstood the situation before and this person was simply doing their best. I see this come up over and over and if you ever catch yourself asking 'why don't they just do this, it’s stupid', it probably means you’re missing some crucial piece of information. So I really think it’s important to read, understand and objectify a situation fully because it is way too easy to get blinded by assumptions.

Working at Massive also taught me about the need of vocalizing yourself. Sometimes it is important to speak up and make your voice heard. Up until this point, I had largely submitted to others, trusting their judgments and following their lead. I came to realize that people enjoy working with others who participate, open up and cooperate with each other. I don’t mean you have to be bullish, but rather that it is important to put your views and opinions forward. You are, after all, hired for your expertise and you need to trust yourself. The work I am most proud of has always come from getting feedback and collaborating with others.“

“My time on Wolfenstein taught me about networking. I’ve now been in the industry for 10 years and worked with many people who have moved around and changed jobs. After Playground, I have not joined a studio where I didn’t know at least one person working there beforehand. Your network naturally grows as you stay in the industry, and it has been vital for my job security. After a certain point, it does become more about who you know and less about your raw talent. Obviously, I’m framing this in a very selfish light. But in reality, it’s a lot less sinister than that. People are friends and simply enjoy working together. I have been compelled to work at my studios because I know the people inside are awesome. Much of the industry works like this, I think. Friends will stick together and aside from being great for your career, it’s just nice to be around people you love. Without a doubt, you need the hard skills to do your job. You are hired for a service after all, and get paid to deliver content, but once you reach a certain threshold, your soft skills start to become more important.”

What was the most important takeaway from creating the Wolfenstein asset packs?

“I think my work on Wolfenstein is probably both the best and worst work I’ve done. I am incredibly proud of the result, especially given the circumstances under which it was built, but I don't think it meets the expectations we had as a team. However, proper planning proved to be the key for us. Without the scribbles on paper to get your ideas across, I think you can easily get side tracked and isolate yourself. I've worked primarily alongside Ivan Martinez for all my time at Machine Games, and he is the guy largely responsible for the kits. While I did do some modular kits, I was focused on texturing and set-dressing more than anything else. For me, working in pairs like this has been the most enjoyable and productive way of working and is something I intend to do as much as possible. My take away from the Wolfenstein packs is simply that I am a better texture artist than environment artist now, and when you find that work buddy who can fix your mess, you hang on to them like a golden goose!”

In your Wolfenstein Substance talk, you describe how you combined modelling, sculpting, simulation and Designer to create complex, layered materials. Do you believe artists can sometimes hinder their potential by aiming for the “100% Substance Designer” bragging rights? Do you have any tips for artists looking to achieve complex materials like these when they’re up against time during production?

“Hinder is perhaps the wrong word to use here. There is great value in pushing yourself and a tool to the limit. This 100% Designer topic seems to really divide people and in the spirit of embracing Swedish culture, I sit firmly down the middle! A lot of the crazy stuff you see coming out is kinda useless for production, this is true. But, you can bet the person had a lot of fun making it and is undoubtedly a better artist for it. I don't see any issue with that myself. It is however important to realize that if you are looking for work, your portfolio needs to showcase the kind of services a company needs and your ability to deliver them. Unfortunately, most games just don't need crazy Substance balls. You don't get to make crazy things at work often, production just isn't like that. This is why I think so many people enjoy making this stuff in their free time. In fact, it's healthy in countering burn out. Everyone I've worked with has understood this. Your free time is for fun and your work is work.

“I don't really have a good answer for what to do when you’re short on time in production. The reality is that sometimes you just simply can't afford to spend the time you want. I would say this is without a doubt the largest contributor to 'bad' game art and is very rarely due to a bad artist. Luckily at Machine Games, they let you schedule yourself entirely. So if I wanted to spend the time and really push an asset, you can. Not everywhere is like this though and if your company tightly controls the reins, then it can be very tough and disheartening to work in. I've found that people respond incredibly well if you show them what they are missing though. Investing a little time on the side to prove how awesome something can be, has worked well to sway the opinions of others for me in the past. It is good to leverage other people’s work too. Before starting the more complex materials for Wolfenstein, I went around the office asking if anyone had some high poly assets that I could use. I couldn't begin to imagine how many hours it would have taken me if I had to make all that stuff myself. Do your research and see if someone has automated part of your problem. For example, the work Simon Verstraete has done with his Houdini tool would have saved me weeks of time, had it been available then.”

Amazing. What I love about talking to Ben is that he’s clearly been around the block and back again about seven times. He’s not only very talented but his answers evidently come from a place of humility. It’s easy to stick your head in the sand and be carried away with learning and mastering software when Ben’s demonstrated that a lot of the real learning comes with time and experience. That’s what’s great about production. To summarise:

Savour your achievements.

Reputation precedes you.

Don’t be too quick to judge: objectify situations.

Speak up and make your voice heard.

Rely on your friends, and be there to be relied upon.

Make plans.

Hold onto the good people.

Free time is for fun and your work is work.

Collab with your colleagues and they might just save you hours or days of your time.

The analogy of starting at base camp, fighting your way up the mountain and finally reaching the summit, only to find another bigger mountain right in front of you is often something artists commonly feel. That’s why I think Ben’s point about savouring your achievements and not beating yourself up about productivity is so important. A career is a marathon, not a sprint.

PRINCIPLE VS LEAD - THE TOP OF THE MOUNTAIN

One of the big challenges for those further along in their careers is the split of responsibilities. Marcel mentioned in the environment art edition that “In games, people climb up the ladder fairly quickly and are often not well prepared for the increase of responsibility.” That’s a topic that is brought up frequently and it’s time to talk about it with someone who knows that road very well. Introducing Principal Material Artist at Probably Monsters and Founder of the Mentor Coalition - the one and only Josh Lynch.

It seems there’s a forked road on the career path of seasoned artists. You either become the in-house expert Principal Artist or you become the managerial, team-building Lead Artist. Can you elaborate on this idea from personal experience? Could you give any guidance for those going through a similar experience?

“Sure! I think as any artist matures in their career this inevitably comes up. Personally I have been a Material Artist in multiple Individual Contributor (IC) roles: senior, staff, principal and a lead material artist on various projects. They all have been unique in ways with a variety of ups and downs. So let's get into it.

As an IC you're primarily creating art which artistically is a fantastically rich experience. As a lead of a material team you are expected to make art as well as run ‘Untitled 3’, your team and everything that comes with that which for me was an extremely rewarding experience- I loved that combination. This might come off as rough but I think it needs to be said that not every artist can be a good lead. Being a good lead requires a skillset that requires patience, empathy, taking a back seat to asset creation and helping your team move forward throughout the production process. While it may not come off as the most glamorous role with respect to your portfolio, being a lead artist can have a massively positive impact on a team and the production.

Installing a lead who is not ready for the role can be an absolute disaster for a project. My guidance and advice on this is to have honest conversations with your family, close friends, leadership at the studio, and last but not least, with yourself. If the studio you are at isn’t meeting your needs it’s more than okay to look elsewhere and explore other options.”

As a Material Artist, what insight or skills do you gain from having a foundational background in environment art?

“There are many facets to this but I will touch on a couple of things.

First, having a foundational background in environment art gives you a big leg up in experience working within the pipeline for which you are making materials. This means you can anticipate the needs of the team because you yourself used to reach for materials and over time formed ideas and opinions on which ones stood out to you. Not just for quality but for functionality. Functionality is a major factor. For example when making trim sheets, you will know from previous experience what functionality the artist might be after. You most likely loved a particular trim sheet from a previous production and therefore understand what made it useful for you.

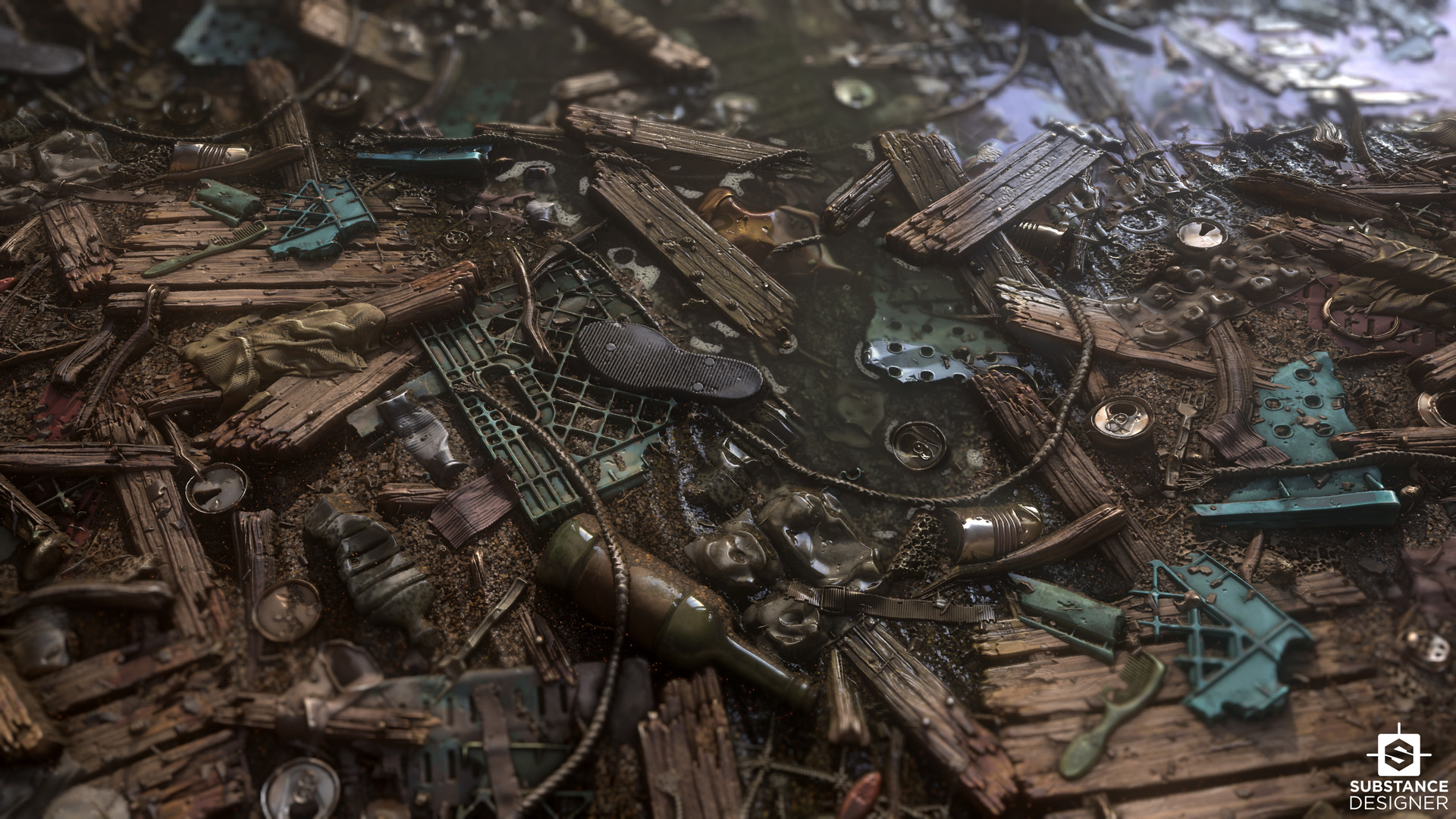

Another thing to consider is bringing balance and cohesion to a scene. This is also an expectation of an environment artist and can translate well to being a material artist. When you are making materials for a level it’s important to think of them as a set that all needs to sit well together. Some materials might be made to look simple for eye rest where some are more complex for pockets of detail. I notice a lot of artists think they need to make these highly complex materials with tons of details and layering of elements. In reality most materials for a game are fairly simple and rely on blends. Here is an example of two simple materials working very well together as a blend even though they are simple on their own:

At the end of the day it is crucial for the material artist to collaborate with the artist requesting a material, be open to feedback and ready for changes. Don't get attached to the art, you are at work, not at home.”

On a previous GDD podcast episode you talked about environments and materials having ‘soul’. Could you explain what that means and what artists can do to layer this into their own work?

“I think what it means is making an artistic decision to push on certain elements and not treating everything like it needs to be a perfect scan or sterile. Emphasize certain things in your material. Push colour variety a bit more, make roughness more than what's typically expected, pack story into the art you are making. It will all add up to something beautiful in the end.”

When you're hiring new material artists, what are you specifically looking for on their portfolios?

“That they are capturing the essence of the material they are presenting. A solid understanding of what each channel of the shader is doing. Control over the height map, layering objects with little to no clipping. Albedos that are samples from scans and not a photo. Roughness maps that bring excitement when the light rolls across a surface. In addition to material quality, control, and storytelling, I’m also looking at how the material is being presented. Rendering and presentation is imperative to getting eyes on your work. I can’t overstate this enough. And as we discussed from the first question, seeing things in context or with a basic blend can go a long way.”

So we’ve reached the summit. We’ve covered the tips and tricks. We’ve covered portfolios vs production. We’ve covered career paths. Now it’s time for the next steps. What’s on the horizon? The price we pay for reaching the summit is the need to adapt.

My next three guests cover three pathways in the world of material art that are likely to become more and more relevant as we move into the next generation of games.

PROPS AND ENVIRONMENTS

First up, we’re talking props with Pierre Fleau, Senior Material Artist at Rockstar Games.

Should the modern Material Artist also be able to create props and build environments?

“I think a material artist is a specialization of an environment artist who needs to understand how to create a full environment to be able to create the textures that will compose it.

As a material artist you are also responsible for a large part of the pixels that make up the final image, so do not hesitate to share your knowledge and give advice to other professionals (eg. how to map certain elements, adapting texel ratio etc.) For that we need to have a global knowledge of asset production.

Creating example models or modules already mapped to represent a kit of objects or buildings is a very good exercise to practice on a daily basis. Sharing this kind of work helps the teams a lot to speed up the work and increase quality. This also avoids unnecessarily creating certain elements which would not be usable later.”

“In addition, the work in a graphic production is very collaborative and we are often led to share tasks, sometimes modeling or level art too, not only with textures and materials. There are so many specialisations in production nowadays that it is always good to extend knowledge and look at different subjects like shader creation, lighting and also how to bake assets or sculpt. This will make a big difference in career advancement and personal enrichment.”

Are Material Artist’s at risk of restricting themselves into only being able to make tileable textures?

“In production we create all kinds of textures. We can easily list textures of landscapes, architecture (tileable x / y) and atlases of patterns and trims (tile x), but also unique elements such as in alpha (vegetations, small elements of details) and decals to add detail and fake textures.

I don't think you should force yourself to just create tileables, but rather be creative in what we add in the textures. You have to think that most of those textures will be used on 3D models. We must think in advance about how this will be applied. Every new asset needs some thinking and maybe a new way of using the textures.

For example, if we want to create a building, it’s good to start by analyzing references to isolate what we want to create (walls, doors, beams, roofs, attachments etc.) and then to think about how we are going to organize and create them in our texture sheets to optimize memory and make work easier, and more pleasant for everyone.

Finally, I would say that tileables represent a large majority of the work. But it is important to know how to be creative and propose original solutions to add detail to assets.”

And speaking of original solutions, there’s nothing more original than real-life data. Of course photogrammetry is not brand new per se, but it is being used more and more and the next artist has plenty of experience. It’s Grzegorz Baran, Senior Environment Artist at Ubisoft Reflections.

PHOTOGRAMMETRY

What can you learn from the photogrammetry process that you just don’t get when making a material from scratch?

“Photogrammetry is the way to capture reality. This way we always get very high quality photorealistic results in quite a reasonable amount of time. Unfortunately, captures are limited to existing and available things for us. Photogrammetry raises the quality bar. What I have learnt from it? That the world is really brown and dusty. That all that bluish shade we think is a part of what we see comes from the sky. That the world without shadows would look very bad :( I also guess you can learn a lot about photography, polarisation, humans, weather and how to fly a drone.”

How do you achieve consistency across photogrammetry assets when the success of each scan depends on so many factors (such as weather and lighting conditions, avoiding unfocussed shots, removing reflections from non-rough surfaces)

“To get consistency across photogrammetry scans you need to fully understand PBR rules and apply them while tweaking the final material. It’s also very important to use physically accurate reference objects for scale (like rulers) and for color (X-Rite Color Checker) and use them for calibration. The easiest way to calibrate colors is to use simple custom white balance. This way you adjust the overall colors to the environment’s lighting. You can go even deeper and utilise all color clips from the checker and this way get really high color accuracy.

It is also good practice to remove unwanted lighting factors. For example during a sunny day you can cast your own shadow with a light reflector, tent or even an umbrella. For close objects or ground surfaces, you can use a ring flash and overwrite existing lighting. This way you can use cross polarisation to remove glare / specularity from a scanned object.

I think it is way harder to maintain consistency with a procedural or traditional approach as this way you can easily see the quality gap between materials made by artists with different skill levels.”

What does the UE5 tech demo imply for material art?

“The UE5 demo sounds like a big, meaningful step forward. It is a moment everyone was dreaming about 20 years ago when I believe the gaming industry has finally caught up with the movie and viz industry. I think the UE5 demo raises the quality bar and turns photogrammetry into a 'must have' tool for any photorealistic production.”

But from all of this I would like to remind everyone - photogrammetry is just a tool - nothing more and nothing less. It is an option to consider and one worth knowing. I would encourage everyone to use it as a tool and try to mix it with other tools and techniques. Be creative, because nothing never is set in stone and the sky is the limit.”

I spoke at length about photogrammetry and real-time engines being the bridge between games and film in Asking the Legends: Lighting Art. Well the third artist in this section has worked in both industries and was kind enough to drop his two cents on both. Cue James Lucas, Texture Artist at Epic Games.

FILM: TEXTURING IN TWO MEDIUMS

You’ve textured for both games and film. What do you think the two industries can learn from each other?

“I think the technologies and workflows used are actually merging at a pretty fast rate. Traditionally Mari was (and generally is) the go-to for texturing in film due to the immense texture sizes and UDIM support required for assets, but with Megascans / Mixer and Substance catching up on features and becoming more innovative, the film industry is starting to adopt these packages in to their pipelines. This in turn makes working between the two industries more possible than ever.

As an artist I would suggest learning the differences between the two, such as texturing UDIM heavy assets in VFX, and creating "more with less" when it comes to game art, as this will definitely secure your position in the future. Game engines are becoming a popular choice for pre-visualisation work in VFX, and more recently "virtual sets" which help reduce the use of green screens. The use of real-time for both of these shows very obvious overlap with the game industry.”

Is the future of material art ultra-detailed scans combined with endless procedural customizability?

“We definitely live in exciting times when it comes to material art. Currently we are seeing procedural tools grow, and scan data becoming more affordable and vastly available. Mixing the two for endless pattern variations with detailed scan surfaces is becoming more common, and tiling ZBrush sculpts are and will continue to be popular methods.

There are often concerns that scan data is going to put texture / material art positions at risk, but I don't believe that will be the case. Roles may shift slightly, and some may even end up falling into the tech artist category, but current standards will continue on. Photogrammetry resources are becoming more readily available, with artists such as Grzegorz Baran dropping a ton of information for free on the process of scanning surfaces, and hardware / software improving, with companies creating products that allow even amateur users to scan something of decent quality.

Another thing I see catching on is the use of AI to process scan data, whether it's for delighting, or tiling very complex surfaces with very few seams or artifacts. The technology is still quite new, but is improving rapidly.”

Get involved with photogrammetry. Stay versatile with tileables, uniquely unwrapped props, trims, environments and have a peep over the entertainment fence into the world of film and virtual production. These seem to be the best way to stay on your toes as a material artist.

Time to bring all this new knowledge home then. What better way to solidify your knowledge than cementing it as content. Jonathan Benainous is an Environment Texture Artist at Naughty Dog and he’s well known for putting out excellent content on what he’s learned over the years.

LESSONS FROM LIVESTREAMS AND MORE

You’ve done GDC, Substance Livestreams as well as podcasts. What have you learned from doing these?

“Since 2014, I have had the opportunity to write quite a lot of articles, breakdowns and tutorials for 3D Artist Magazine, 80 Lvl, or Substance Academy. It was originally to share my knowledge and help out the community.

Each time I found it more and more useful for myself to do these exercises as it helped me to go through my whole process of creation. Sometimes it was also a good way for me to notice mistakes or ways of improvement, and overall a great reminder. Giving talks is an extension of this. You're still sharing your knowledge, but it's more like teaching or giving a masterclass. You have a real interaction with the audience and it's live, which makes it pretty great to do.

What I've learnt from it is to be able to explain extremely complex things with a few words or steps. Being able to convert a very complex material into a checklist of tasks to do and show to the audience that anybody can do it by staying organized and efficient.

Overall it helped me to learn how to teach and transmit my knowledge in a better way.”

Could you explain what separates the work of a Junior compared to a Senior Material Artist?

“The main difference is that senior material artists have experience in production.”

“According to the art direction and after a look at an environment, you should be able to compose a breakdown of the different techniques needed to achieve the texturing of that scene. Most of the time, you'll go straight to the point and pick the best solution without losing time as you've probably dealt with this on a previous occasion or project.

Junior material artists would probably try different options before to find the suitable solution.

Mentoring juniors is also part of the job of a senior material artist, as you want to help them find the best approach. This is definitely something that I love in my job- sharing my knowledge with artists, exchanging tips and tricks, or discussing best practices. This is a totally valuable way to make you and your teammates level up.”

What’s the most rewarding part about material art?

“For me, the most rewarding part is when you see a grey block placeholder turn into a real environment. [We can do this by] mixing up materials together using height information and creating variations with vertex alpha / colors, or, using a combination of blends, mesh decals, or trim textures to achieve an intricate environment.

What I like the most is being able to add all the tiny kinds of details that I see when I walk around in the street. Like twigs, leaves, pebbles, cracks, etc. Breaking the repetition in a roughness map by adding scratches and imperfections or adding small pebbles and subtle dirt layers to make the materials appealing from every distance. Having that extra layer of realism really makes the difference and brings some life to the game you're working on.”

And the opposite, what’s the most frustrating part of material art and how do you overcome it?

“Being a texture artist might be frustrating sometimes, especially if you just stay focused on your daily tasks but personally I directly work with level artists and modelers to share my knowledge as a material expert but also as a former environment artist.

I provide advice, best practices and feedback to get the best results. My aim is not only to make good textures but to be sure that the environment I'm working on reaches the next level of quality. I'm also directly discussing with leads and directors for follow-ups and making sure to spread their vision at large with the teams.”

Jonathan continues to put out great content that other artists can learn from. I’ve always felt this was a rite of passage. You’re trying to get somewhere, you look up, someone offers you a helping hand, you climb, you celebrate, then you look down at where you were and help the next person up.

James Ritossa is my final guest and is a Surfacing Artist at 343 Industries. James climbed through the game artist ranks at an early age and has some very interesting insights on where the artform might be looking forward to wrap up with.

THE FUTURE OF MATERIAL ART

What has it been like working in the games industry from such a young age?

“Sometimes I find it a bit difficult to answer this question because it’s one of those things that I just found myself doing from a very young age because I enjoyed it. I started doing 3D art for mods like Arma and Squad when I was about 14 years old and then started working professionally as a freelancer when I was 15. Then when I was 18, I got a very brief internship at Allegorithmic, then a month later I was at Avalanche Studios in NYC. It has been an awesome, wild ride so far, and I could not be more happy to be working with such an awesome team over at 343 Industries now. If anything, working at my age has been nothing short of amazing. I have never been judged based on my age or “experience”, but rather my work which is something very unique to games, and I am incredibly proud of that type of culture. So would I recommend it? Absolutely! But for some people, college or university is the right choice, and I want people to be aware that there is no proper way of doing things and both paths are totally fine.”

What words of advice would you give yourself looking back on your journey so far?

“I would emphasize the focus on always learning and always working at your craft. A lot of the schools I visit now and again seem to miss the emphasis on working outside of work (or class). In a competitive industry like ours, that is pretty dangerous. I have seen a multitude of artists who began getting stubborn or started to not practice outside of work/school and are now unable to find jobs. So I think the main thing I would say to myself or anyone getting started is to always be willing to learn from other people and to keep your ego out of your head. Spend as much money on tutorials as you would on coffee every month because you are sure to gain that money back in multitudes later on if you listen and take in the information from those lessons.”

Where do you think material art will be in 5 years?

“I think this is one of my favorite questions because it is so hard to say, especially when you think that 5 years ago people were still doing their texturing in Photoshop. That being said, I think the next 5 years are going to be very exciting. I think we will see a lot more emphasis on combining software like Houdini, Substance Designer, and Marvelous Designer when authoring materials. I also think there will be some major advancements in photo-scanning technologies to improve efficiencies and workflows - this is something I am really curious about exploring myself.

Lastly, and most interesting to me right now is where advancements in areas like Deep Learning and Texture Synthesis will be taking us. Nvidia has shown some really interesting technologies in their past tech demos at Siggraph which amaze me every year. Seeing how these new and emerging technologies could affect tedious tasks in photo-scanning pipelines such as denoising, delighting, and scan cleanup and even increasing image resolution has me very excited for the future. I think one important thing for every artist to understand is that this line of work is only becoming more technical.

It’s time to start valuing art fundamentals just as much as technical fundamentals, because that seems to be the way the industry is heading, or at least in my mind it is :)”

OUTRO

Fin. Thanks for rounding that out James.

This has been a bulky read so I appreciate you taking the time to read, whether it was for 5 minutes or 50. Thank you. Extended thanks to the artists I interviewed for this one who had invaluable insight into the life cycle of material art. If you found it valuable then please share the article to someone who might find it useful. Until next time EXP readers!

Kieran Goodson - Junior Environment Artist at Rebellion | Twitter | Instagram | LinkedIn | Discord: AnHourOfWolves#9100